Inside Track: In Memoriam, Ken Ishiwata

Ken Ishiwata was undoubtedly one of the greatest characters to grace the modern hi-fi world. He was a huge personality, yet emerged from a time and a place – postwar Japan – that had little time for such exuberance. It wasn’t ego that made him stand out from the crowd, but rather his immense passion for music, hi-fi and design. Indeed Ken was actually a quiet, gentle and modest man who sometimes seemed uncomfortable with his transition into something approaching hi-fi’s very own rock star.

Having spent a good deal of time with him over the past quarter-century – on press trips, product launches and propping up late night hotel bars – two things about him impressed most. First was his incredible knowledge of hi-fi and electronics, right down to component level. He had spent a huge amount of time listening to individual brands of capacitors, resistors and transistors. He was an early advocate of the now near-universally accepted notion that individual components have their own distinct sounds. Back in the nineties, this was still pretty controversial stuff, and people who espoused the idea were often mocked.

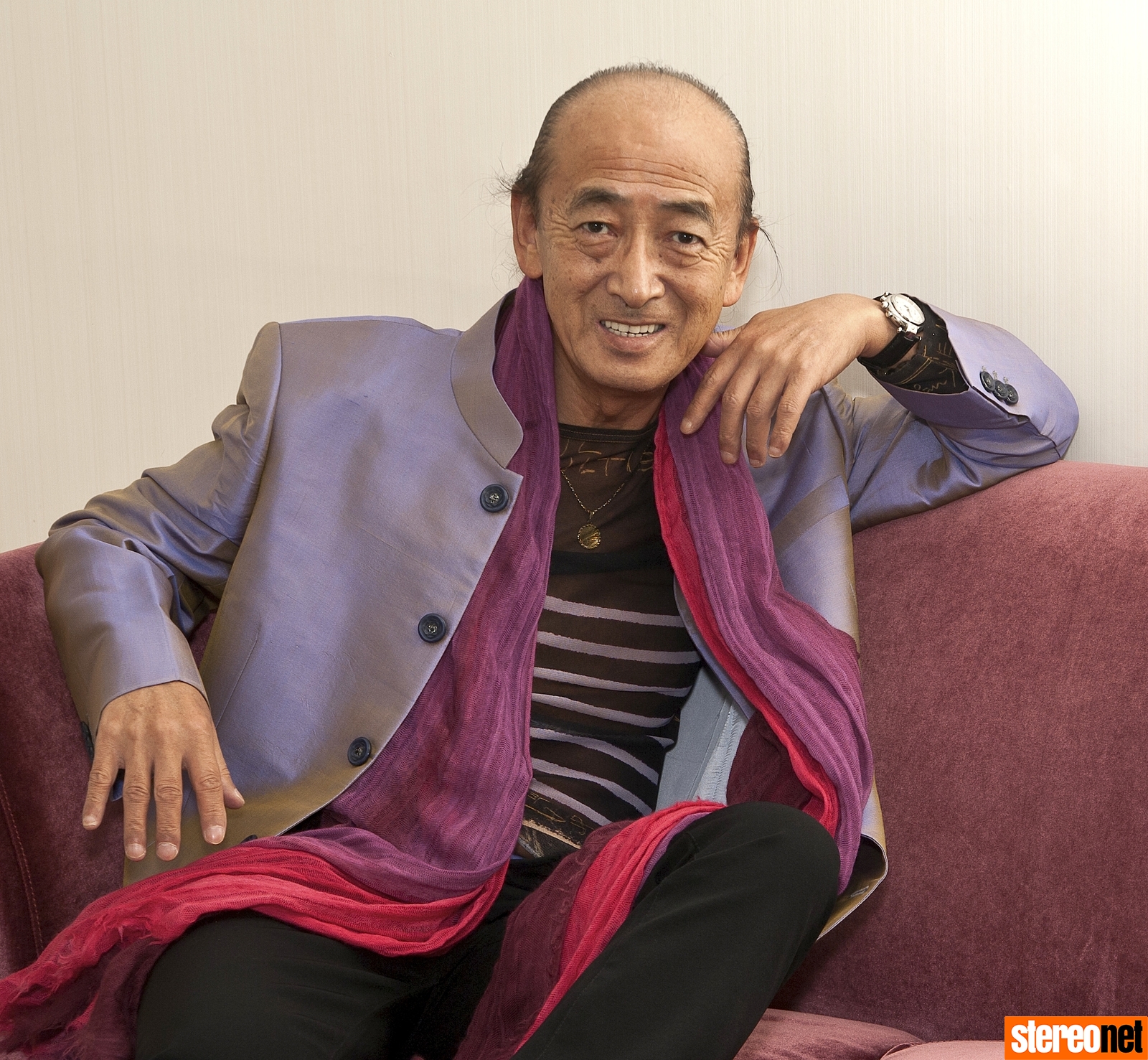

Second, beyond his extensive knowledge of his subject, he had a hinterland – a life beyond his career. Of course, he was at heart an engineer who loved making, modifying and designing things. Yet he was fascinated by couture; indeed Ken spent much of his later life in Antwerp, Belgium – the epicentre of Europe’s style scene – and had friends in the top echelons of the global fashion industry. He loved designing his own clothes and wore them very well. By the early nineties, he had become famous for his drainpipe black trousers, collarless shirt and brightly coloured satin jacket look – plus his tightly tensioned ponytail. In the winter months, he would often be seen wearing a scarf that matched his jacket – also specially designed by him. As for his passion for music – especially female jazz vocalists – that was immense, and he was a keen recorder of live music too.

Among a great many other things, Ken loved fast cars and owned plenty over the years. Some of these – like his Fiat X1/9 – he admitted to having crashed in his younger days. In later life, he was a big fan of BMW 650 coupes, and once drove me from Eindhoven – Marantz’s European headquarters – down to see his close friend Karl-Heinz Fink in Essen, banging the car on and off its 255km/h speed limiter for much of the way. My only surprise was that he hadn’t removed it – because, as everyone who met him knew, his great catchphrase was “special modification.”

THE SPECIAL ONE

Around the turn of the new millennium, Ken and I were sat at a hotel bar in San Sebastián, talking tubes as you do. We were both serious valve amplifier fans, and back then this was very much a minority view. So we enthusiastically swapped stories about our favourite brands and vintages of valves, with me very much in ‘receive’ mode and Ken in ‘transmit’, of course. Then my mobile phone rang, so I hastily pulled it out of my pocket to switch it off, lest I miss a valuable nugget of his knowledge. It was a brand new Nokia, of which I was very fond, and Ken looked at it and said, “yes, I have this one too.” He then pulled his phone out of his pocket, but I didn’t recognise it at first. Instead of the grey case and dim white display, his was in Marantz champagne gold with bright blue LEDs. “Special modification”, he said with a smile.

The most important special modifications that Ken Ishiwata ever did were to budget Marantz CD players, however. “The high point of my career at Marantz is without doubt the Ken Ishiwata Signature CD player series”, he told me last year. “The CD-63 KI Signature is a classic – many hi-fi reviewers still keep these in their collections. It’s not the most neutral sounding machine, but it has a very special sexy sound. What many don’t know is that I did these modifications to many Marantz products, going back to the LD-50 loudspeaker system, at the end of the nineteen seventies.”

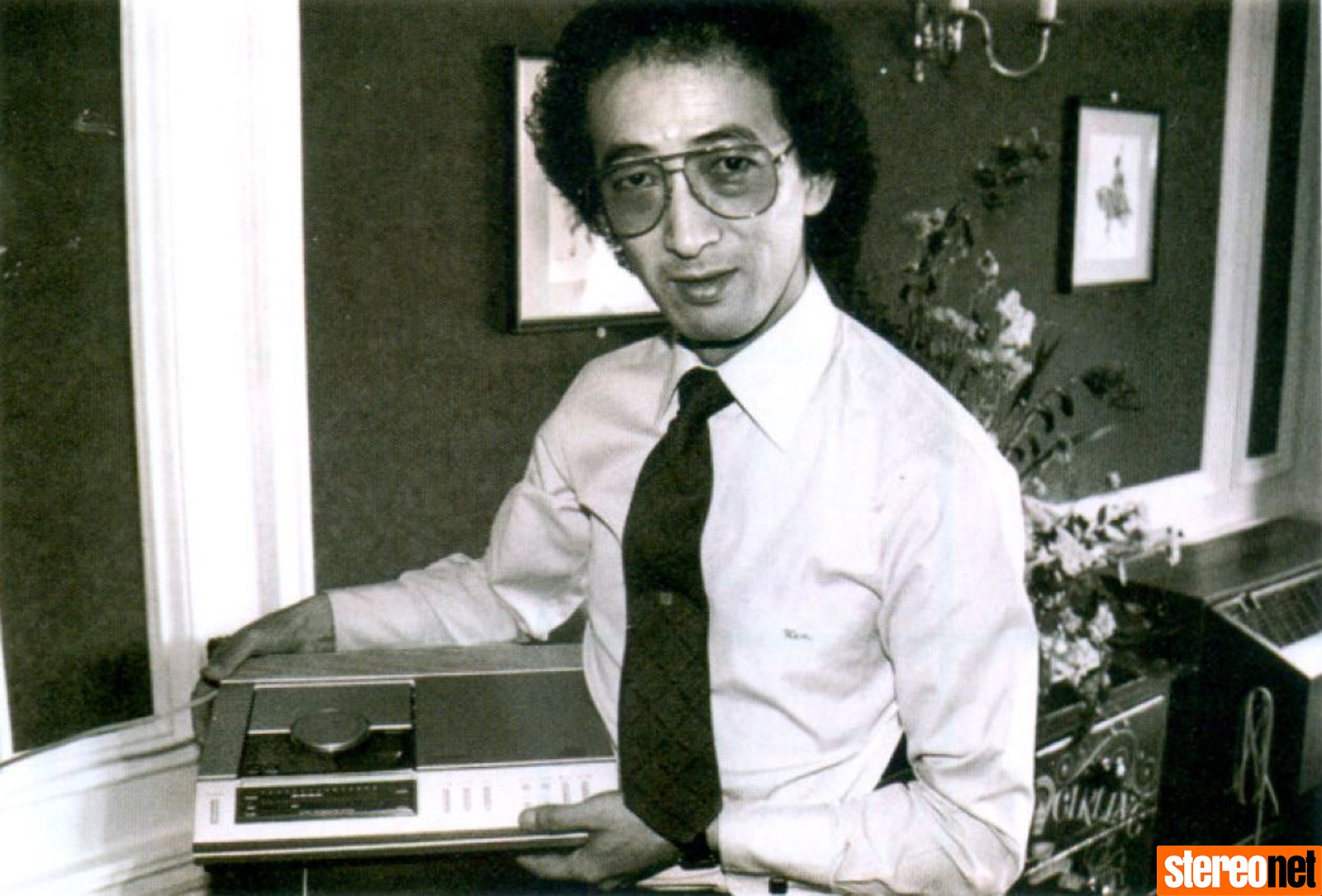

Ken’s first job at Marantz in 1978 was solving the problem of misunderstanding between the Japanese engineering group and European quality control department. “I learned so much by doing this, then I turned my attention to loudspeakers, and then electronics.” He had been building both since his early teens back in Japan, so was very much in his element. Indeed Ken crafted his very own copy of the iconic Marantz Model 7C preamplifier, having borrowed one from his father’s friend to reverse engineer. He told me that he couldn’t afford premium components so used the cheapest generic capacitors, diodes and resistors he could find. “I was so shocked to discover it didn’t sound anywhere near as good as the real thing!”, he once told a group of journalists. “That was down to component quality.”

When asked to look at Marantz electronics in the late nineteen seventies, Ken realised that the sound wasn’t at all like the classics of the fifties and sixties. “So I began to talk to Marantz Japan about this and involve myself in the product design. This led to me starting to work on CD players. Compact Disc came in, and things changed forever. Actually, the new Red Book CD standard wasn’t good enough for really high level sound, but we understood that it had to be set where a big company could make a product at a reasonable price. At the time, I didn’t know anything about digital audio at all, so it was fantastic to learn from the masters at Philips. It informed the knowledge and experience behind my Special Edition CD players.”

MUSIC FOR THE MASSES

The original Philips CD100 – the company’s first-ever silver disc spinner – was a good machine, but when the Marantz version came out, it had some modifications to improve it further. “We made some changes to the power supply and in the digital filter. We were very happy with the results. To be honest, rival machines like the Sony CDP-101 were no comparison! Then, technology progressed and Philips eventually came out with their 16-bit, four times oversampling chips. At that time, we had about three thousand CD-45s sitting in the warehouse in the UK, and the managing director asked what we were going to do with them. ‘Maybe we should sell them for ninety-nine pounds?’ The marketing manager didn’t want that, but it seemed like we had no choice. So I said, ‘Wait a minute, I am going to modify these 14-bit machines, and I’m going to make the most musical CD player available, and then we’re going to sell them for fifty pounds more!’ We finally decided on a limited edition run of two thousand. I did my modifications and took a prototype to a classical musician friend of mine, and he was amazed. So it came out – and they all sold out without in two weeks. We said, ‘what a pity we didn’t have more machines to modify!’ That was the birth of the Special Edition.”

From then on, there was no turning back, and Marantz enjoyed a purple period in the nineties when it defined itself the purveyor of budget audiophile products that sounded better than their price rivals. “After the CD-45LE, we did the CD-65 and CD-75 Special Edition, and then every year we had a new model – like the CD-50SE, CD-52SE, CD-63SE, CD-67SE and CD-6000OSE. Each generation didn’t have a new chipset – until 1989 when Bitstream arrived – because fundamentally the digital filter was working very well. But we did change the mechanisms, the CD100 had a CDM0 type mech, and the CDM1 followed. This was the original swing-arm transport, complete with diecast parts. These had better trackability compared to the linear tracking designs the Japanese manufacturers were using. But this did have its problems – it was heavy, and the position control was done by servos which required high current, and this affected the noise floor. We ran with swing-arms through the CDM3 and CDM4 right up to CDM9. After that, it was linear, parallel-tracking like the Japanese. Those early Philips/Marantz machines always sounded very different from the Japanese rivals because they had better swing-arm transports and superior 4x oversampling DACs and digital filters. Even our S/PDIF chip was better – that early Philips S/PDIF chip was the best one ever made.”

TILL THE END

Ken grew up as a great fan of Saul B. Marantz, but by the time he joined the company, it was in the process of transitioning from a heritage high-end US brand to a modern digital specialist owned by Philips. This was not without its challenges, and Ken found himself on the receiving end of some unwanted corporate politicking. “When Philips took over, Marantz sales went down because of the change in distribution networks – and they forced us to change product development. The new products were not at all traditional Marantz designs, and we lost out in our own markets. By 1990 we were really in trouble – but then we took the company back from Philips and turned it from a big loss-making business to break-even in just one year!”

Indeed, he had a number of fights with management throughout his career. “At one point the Japanese Marantz people wanted to stop us making stereo separates and move to AV – but I said, “no way, we cannot stop being who we are!” I insisted that we kept the two-channel business going, and made sure we developed strong products that gained market share and contributed strongly to our bottom line. After some years, the Japanese management thanked me for this strategy, acknowledging that I helped to keep the business running. Over my career I have learned many lessons, but sadly haven’t always been in a position to change the decisions. One good one is – if it isn’t broken then don’t fix it! My greatest personal sadness is that I was too big-headed to fight against the Japanese management over the use of my name in domestic market products. I was up against a senior company man, and I wasn’t diplomatic enough. This resulted in there being no Ken Ishiwata Signature products in my home country of Japan, which is my one big regret – and so I do wish I had handled the company politics differently…”

The news that Ken Ishiwata had left Marantz after over forty years in the job back in May 2019 amazed many. Industry insiders were incredulous that the company’s brand ambassador – and an iconic design engineer with vast experience and expertise – was somehow ‘let go’. Although Ken showed great dignity over the whole affair, it was clear that he thought he had been poorly treated and felt a real sense of loss. He told me personally that, “it is really hard for me to forget this special relationship with Marantz. I still remember very well what Saul B. Marantz told me when CD came into our world. He said he had done everything with LP and tubes, and now it was my turn to make something of Compact Disc…”

It is tragic that Ken’s life after Marantz was so short. Upon his sudden departure from the company, he confided to me that, “At this moment I’m not certain what I’m going to do next… it’s very hard for me to break the emotional ties that I have. A few people are already asking me to help them, and others are even asking how much I would charge if they want my name on their products…” On the day of the announcement of his death, his long term friend and co-conspirator Karl-Heinz Fink told me that, “Ken did not plan to retire, and was busy already creating something new and continuing to make products the way he wanted them to be. It is so sad that he could not finish them. His idea was to work with me, but I kept it secret because I didn’t want him to be a marketing horse for us. He did it out of friendship. The new project would have been done here in Essen, but again it is too early to talk about. I would love to finish it…”

Finally, some parting words from what was to be my last formal interview with Ken last year. “I must thank Saul B. Marantz for opening my eyes – and ears – to really know what stereo reproduction is, with the Model 7C when I was high school student. I never thought that one day I would work for the company and do what I have done for the brand. Maybe it was fate. I always gained knowledge from doing something, and that always made such a big difference in my life. My last forty years have been so interesting. As I always say, music is the highest form of art we humans have created! There is nothing else that has the power to touch people so strongly.”

Ken Ishiwata, 1947–2019

David Price

David started his career in 1993 writing for Hi-Fi World and went on to edit the magazine for nearly a decade. He was then made Editor of Hi-Fi Choice and continued to freelance for it and Hi-Fi News until becoming StereoNET’s Editor-in-Chief.

JOIN IN THE DISCUSSION

Want to share your opinion or get advice from other enthusiasts? Then head into the Message

Forums where thousands of other enthusiasts are communicating on a daily basis.

CLICK HERE FOR FREE MEMBERSHIP

Trending

applause awards

Each time StereoNET reviews a product, it is considered for an Applause Award. Winning one marks it out as a design of great quality and distinction – a special product in its class, on the grounds of either performance, value for money, or usually both.

Applause Awards are personally issued by StereoNET’s global Editor-in-Chief, David Price – who has over three decades of experience reviewing hi-fi products at the highest level – after consulting with our senior editorial team. They are not automatically given with all reviews, nor can manufacturers purchase them.

The StereoNET editorial team includes some of the world’s most experienced and respected hi-fi journalists with a vast wealth of knowledge. Some have edited popular English language hi-fi magazines, and others have been senior contributors to famous audio journals stretching back to the late 1970s. And we also employ professional IT and home theatre specialists who work at the cutting edge of today’s technology.

We believe that no other online hi-fi and home cinema resource offers such expert knowledge, so when StereoNET gives an Applause Award, it is a trustworthy hallmark of quality. Receiving such an award is the prerequisite to becoming eligible for our annual Product of the Year awards, awarded only to the finest designs in their respective categories. Buyers of hi-fi, home cinema, and headphones can be sure that a StereoNET Applause Award winner is worthy of your most serious attention.